Efficient Market Hypothesis: Is the Market Efficient at all?

In finance, the efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) asserts that financial markets are “informationally efficient”. That is, one cannot consistently achieve returns in excess of average market returns on a risk-adjusted basis, given the information publicly available at the time the investment is made. The validity of the hypothesis has been questioned by critics who blame the belief in rational markets for much of the financial crisis of 2007–2010. Defenders of the EMH caution that conflating market stability with the EMH is unwarranted; when publicly available information is unstable, the market can be just as unstable. But then the question is, how will the investors know when the information is good, and when it is not? How will the investors remain rational while controlling their greed and fear?

Few months ago, an article appeared about how the free markets sank the US economy. All over again we are making the assumption that we have free markets and they are somehow rational. Is it time to question these assumptions?

By Elliott Wave International

Of all the belief systems of Wall Street, few can claim the devoted following of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, the idea that stock prices adhere to the same laws of supply-and-demand that govern retail products. Once coined the theoretical “Parthenon” of economics, this notion has consistently endured the test of time – until now. Academics and advisors across the globe are currently exposing crack after crack in the “Efficient” model so deep as to bring the entire theory crashing to the ground.

“The EMH is not only dead,” writes a July 29, 2010 news source. “It’s really, most sincerely dead.” (Minyanville)

As to what caused the theory’s collapse — one recent business journal offers this insight:

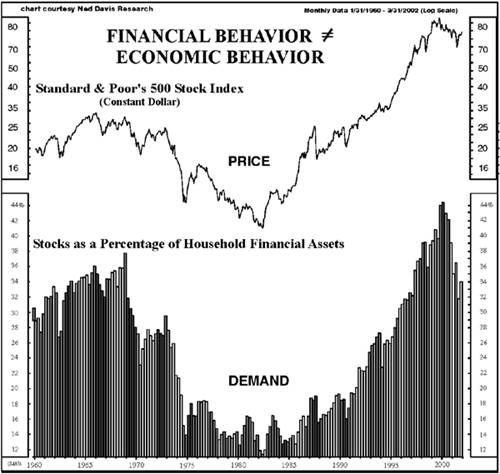

“Financial markets do not operate the same way as those for other goods and services. When the price of a television set or software package goes up, demand for it generally falls. When the prices of a financial asset rises, demand generally rises.” (The Economist)

Here’s the thing. Six years ago, Elliott Wave International president Bob Prechter pronounced the exact same finding in his April 2004 Elliott Wave Theorist. (Read that full-length publication today, absolutely free by clicking on the hyperlink) In that groundbreaking report, Bob presented the compelling picture below that shows how investors increase their percentage of stock holdings as prices rise, and decrease them as prices fall:

|

The next question is why? Answer: Motivation: i.e. the purchase of goods and services is about need; while the purchase of stocks is about desire. Here, Bob Prechter’s 2004 Theorist takes the rein:

“The fact is that everyday in finance, investors are uncertain. So they look to the herd for guidance. Because herds are ruled by the majority — financial market trends are based on little more than the shared mood of investors — how they feel — which is the province of the emotional areas of the brain (limbic system), not the rational ones (neocortex)… Buyers, in a rising market appear unconsciously to think, ‘The herd must know where the food is. Run with the herd and you will prosper.’ Sellers in a falling market appear to unconsciously think, ‘The herd must know that there’s a lion racing toward us. Run with the herd or you will die.'”

Prechter and contributor Wayne Parker then expanded on his landmark observation in the 2007 Journal of Behavioral Finance. (Also available, absolutely free by clicking on the hyperlink)

In the end, it’s not enough to just tear down the long-standing EMH. One must build another, more accurate model up in its place. And in the 2004 Theorist, Bob Prechter does just that with the Wave Principle, which reconciles the technical and psychological sides of stock market behavior into this key point: Herding impulses, while not rational, are also NOT random. They unfold in clear and calculable wave patterns as reflected in the price action of financial markets.

As the mainstream media continues to jump on board Prechter’s Financial/Economic Dichotomy Theory, you can read both of Prechter’s original writings. Enjoy your complimentary access to the 2004 April 2004 Elliott Wave Theorist and the 2007 Journal of Behavioral Finance.

Read some of the latest nuggets directly from Robert Prechter – FREE. Click here to download a free report packed with recent quotes from Prechter’s Elliott Wave Theorist.

Efficient Market Hypothesis: True “Villain” of the Financial Crisis?

August 26, 2009

By Robert Folsom

Editor’s Note: The following article discusses Robert Prechter’s view of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. For more information, download this free 10-page issue of Prechter’s Elliott Wave Theorist.

When a maverick idea becomes vindicated, there’s a good story to tell. It usually involves a person (or small group of people) who courageously challenge the orthodoxy of the day — and, over time, the unorthodox yet better idea prevails.

A “good story” of this sort has surfaced during the current financial crisis. A chapter of the story appeared in a recent New York Times article, “Poking Holes in a Theory on Markets.” The theory in question is the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), which the article suggested is so hazardous that it “is more or less responsible for the financial crisis.” This quote tells you most of what you need to know:

- “In the last decade, the efficient market hypothesis, which had been near dogma since the early 1970s, has taken some serious body blows. First came the rise of the behavioral economists, like Richard H. Thaler at the University of Chicago and Robert J. Shiller at Yale, who convincingly showed that mass psychology, herd behavior and the like can have an enormous effect on stock prices — meaning that perhaps the market isn’t quite so efficient after all. Then came a bit more tangible proof: the dot-com bubble, quickly followed by the housing bubble. Quod erat demonstrandum.”

In case your Latin is rusty, Quod erat demonstrandum means “which was to be demonstrated.” Its abbreviation (QED) appears at the conclusion of a mathematical proof. In this case, the massive financial bubbles of recent years are the proof that refutes the efficient market hypothesis, which argues that markets move in a “random walk” and are not patterned.

Similar articles in the financial press have reported the demise of the EMH. Just this week an Economist magazine blog included this bold declaration:

“No one has yet produced a version of the EMH which can be tested and fits the evidence. Thus, the EMH must logically be discarded, as a valid hypothesis must be testable.”

QED, indeed — I agreed years ago that the random walk was implausible. But I didn’t come to this view because of behavioral economists, although their work over the past decade has certainly been valuable. Instead, I was persuaded by the work of someone who first challenged the financial orthodoxy more than three decades ago, specifically April 1977. As a young technical analyst at Merrill Lynch in New York, his research circulated among several of Merrill’s clients. His name for these studies was the Elliott Wave Theorist: the April ’77 study was a detailed analysis of the 1975-76 stock market, which offered this comment on the random walk model:

- “If market moves are arbitrary (as the random walk proponents suggest), then internal components would rarely ‘make sense’ mathematically, and then only by statistically insignificant fluke occurrences. However, there seems to be enough evidence that mass psychology, as recorded in the Dow Jones Industrials, form patterns that are uncannily interrelated….At least this much can be fairly reliably stated as a result of this work: This idea that the market is a ‘random walk’ is probably false.”

Robert Prechter left Merrill soon after; he has published the Elliott Wave Theorist in every month since. Every issue has, in one way or another, “convincingly showed that mass psychology, herd behavior and the like can have an enormous effect on stock prices.”

So while there may be a good story to tell about behavioral economists, I trust you see why I believe there is a vastly better one to tell.

The “enormous effect” of “mass psychology” and “herd behavior” is exactly what explains the financial downturn that began in late 2007. Prechter’s Elliott Wave Theorist anticipated the crisis and warned subscribers beforehand. Likewise, he alerted them to the bear market rally that began last March.

For more information from Robert Prechter, download a FREE 10-page issue of The Elliott Wave Theorist. It challenges current recovery hype with hard facts, independent analysis, and insightful charts. You’ll find out why the worst is NOT over and what you can do to safeguard your financial future.

Robert Folsom is a financial writer and editor for Elliott Wave International. He has covered politics, popular culture, economics and the financial markets for two decades, via print, radio and the Internet. Robert earned his degree in political science from Columbia University in 1985.