What Can Movies Tell You About the Stock Market?

The following article is adapted from a special report on “Popular Culture and the Stock Market” published by Robert Prechter, founder and CEO of the technical analysis and research firm Elliott Wave International. Although originally published in 1985, “Popular Culture and the Stock Market” is so timeless and relevant that USA Today covered its insights in a Nov. 2009 article. For the rest of this revealing 50-page report, download it for free here.

This year’s Academy Awards gave us movies about war (The Hurt Locker), football (The Blind Side), country music (Crazy Heart) and going native (Avatar), but nowhere did we see a horror movie nominated. In fact, it looks like Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street was the most recent to be nominated in 2008, for art direction (which it won), costume design and best actor, although the last one to win major awards for Best Picture, Director, Actor and Actress was The Silence of the Lambs in 1991.

Whether horror films win Academy Awards or not, they tell an interesting story about mass psychology. Research here at Elliott Wave International shows that horror films proliferate during bear markets, whereas upbeat, sweet-natured Disney movies show up during bull markets. Since the Dow has been in a bear-market rally for a year, now is not the time for horror films to dominate the movie theaters. But their time will come again.

In the meantime, to catch up on why all kinds of pop culture — including fashion, art, movies and music — can help to explain the markets, take a few minutes to read a piece called Popular Culture and the Stock Market, which Bob Prechter wrote in 1985. Here’s an excerpt about horror movies as a sample.

From Popular Culture and the Stock Market by Bob Prechter

- While musicals, adventures, and comedies weave into the pattern, one particularly clear example of correlation with the stock market is provided by horror movies. Horror movies descended upon the American scene in 1930-1933, the years the Dow Jones Industrials collapsed. Five classic horror films were all produced in less than three short years. Frankenstein and Dracula premiered in 1931, in the middle of the great bear market. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde played in 1932, the bear market bottom year and the only year that a horror film actor was ever granted an Oscar. The Mummy and King Kong hit the screen in 1933, on the double bottom. These are the classic horror films of all time, along with the new breed in the 1970s, and they all sold big. The message appeared to be that people had an inhuman, horrible side to them. Just to prove the vision correct, Hitler was placed in power in 1933 (an expression of the darkest public mood in decades) and fulfilled it. For thirteen years, lasting only slightly past the stock market bottom of 1942, films continued to feature Frankenstein monsters, vampires, werewolves and undead mummies. Ironically, Hollywood tried to introduce a new monster in 1935 during a bull market, but Werewolf of London was a flop. When film makers tried again in 1941, in the depths of a bear market, The Wolf Man was a smash hit.

- Shortly after the bull market in stocks resumed in 1942, films abandoned dark, foreboding horror in the most sure-fire way: by laughing at it. When Abbott and Costello met Frankenstein, horror had no power. That decade treated moviegoers to patriotic war films and love themes. The 1950s gave us sci-fi adventures in a celebration of man’s abilities; all the while, the bull market in stocks raged on. The early 1960s introduced exciting James Bond adventures and happy musicals. The milder horror styles of the bull market years and the limited extent of their popularity stand in stark contrast to those of the bear market years.

- Then a change hit. Just about the time the stock market was peaking, film makers became introspective, doubting and cynical. How far the change in cinematic mood had carried didn’t become fully clear until 1969-1970, when Night of the Living Dead and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre debuted. Just look at the chart of the Dow [not shown], and you’ll see the crash in mood that inspired those movies. The trend was set for the 1970s, as slice-and-dice horror hit the screen. There also appeared a rash of re-makes of the old Dracula and Frankenstein stories, but as a dominant theme, Frankenstein couldn’t cut it; we weren’t afraid of him any more.

- Hollywood had to horrify us to satisfy us, and it did. The bloody slasher-on-the-loose movies were shocking versions of the ’30s’ monster shows, while the equally gory zombie films had a modern twist. In the 1930s, Dracula was a fitting allegory for the perceived fear of the day, that the aristocrat was sucking the blood of the common people. In the 1970s, horror was perpetrated by a group eating people alive, not an individual monster. An army of dead-but-moving flesh-eating zombies devouring every living person in sight was a fitting allegory for the new horror of the day, voracious government and the welfare state, and the pressures that most people felt as a result. The nature of late ’70s’ warfare ultimately reflected the mass-devouring visions, with the destruction of internal populations in Cambodia and China.

Learn what’s really behind trends in the stock market, music, fashion, movies and more… Read Robert Prechter’s Full 50-page Report, “Popular Culture and the Stock Market,” FREE

Popular Culture and the Stock Market

By Robert Prechter, CMT

Popular Culture and the Stock Market

Both a study of the stock market and a study of trends in popular attitudes support the conclusion that the movement of aggregate stock prices is a direct recording of mood and mood change within the investment community, and by extension, within the society at large. It is clear that extremes in popular cultural trends coincide with extremes in stock prices, since they peak and trough coincidentally in their reflection of the popular mood. The stock market is the best place to study mood change because it is the only field of mass behavior where specific, detailed, and voluminous numerical data exists. It was only with such data that R.N. Elliott was able to discover the Wave Principle, which reveals that mass mood changes are natural, rhythmic and precise. The stock market is literally a drawing of how the scales of mass mood are tipping. A decline indicates an increasing ‘negative’ mood on balance, and an advance indicates an increasing ‘positive’ mood on balance.

Trends in music, movies, fashion, literature, television, popular philosophy, sports, dance, mores, sexual identity, family life, campus activities, politics and poetry all reflect the prevailing mood, sometimes in subtle ways. Noticeable changes in slower-moving mediums such as the movie industry more readily reveal changes in larger degrees of trend, such as the Cycle. More sensitive mediums such as television change quickly enough to reflect changes in the Primary trends of popular mood. Intermediate and Minor trends are likely paralleled by current song hits, which can rush up and down the sales charts as people change moods. Of course, all of these media of expression are influenced by mood changes of all degrees. The net impression communicated is a result of the mix and dominance of the forces in all these areas at any given moment.

Fashion:

It has long been observed, casually, that the trends of hemlines and stock prices appear to be in lock step. Skirt heights rose to mini-skirt brevity in the 1920’s and in the 1960’s, peaking with stock prices both times. Floor length fashions appeared in the 1930’s and 1970’s (the Maxi), bottoming with stock prices. It is not unreasonable to hypothesize that a rise in both hemlines and stock prices reflects a general increase in friskiness and daring among the population, and a decline in both, a decrease. Because skirt lengths have limits (the floor and the upper thigh, respectively), the reaching of a limit would imply that a maximum of positive or negative mood had been achieved.

Movies:

Five classic horror films were all produced in less than three short years. ‘Frankenstein’ and ‘Dracula’ premiered in 1931, in the middle of the great bear market. ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’ played in 1932, the bear market bottom year, and the only year that a horror film actor was ever granted an Oscar. ‘The Mummy’ and ‘King Kong’ hit the screen in 1933, on the double bottom. Ironically, Hollywood tried to introduce a new monster in 1935 during a bull market, but ‘Werewolf of London’ was a flop. When filmmakers tried again in 1941, in the depths of a bear market, ‘The Wolf Man’ was a smash hit. These are the classic horror films of all time, along with the new breed in the 1970’s, and they all sold big. The milder horror styles of bull market years and the extent of their popularity stand in stark contrast. Musicals, adventures, and comedies weave into the pattern as well.

Popular Music:

Pop music has been virtually in lock-step with the Dow Jones Industrial Average as well. The remainder of this report will focus on details of this phenomenon in order to clarify the extent to which the relationship (and, by extension, the others discussed above) exists.

As a 78-rpm record collector put it in a recent Wall Street Journal article, music reflects ‘every fiber of life’ in the U.S. The timing of the careers of dominant youth-oriented (since the young are quickest to adopt new fashions) pop musicians has been perfectly in line with the peaks and troughs in the stock market. At turns in prices (and therefore, mood), the dominant popular singers and groups have faded quickly into obscurity, to be replaced by styles which reflected the newly emerging mood.

The 1920’s bull market gave us hyper-fast dance music and jazz. The 1930’s bear years brought folk-music laments (‘Buddy, Can You Spare a Dime?’), and mellow ballroom dance music. The 1932-1937 bull market brought lively ‘swing’ music. 1937 ushered in the Andrews Sisters, who enjoyed their greatest success during the corrective years of 1937-1942 (‘girl groups’ are a corrective wave phenomenon; more on that later). The 1940’s featured uptempo big band music which dominated until the market peaked in 1945-46. The ensuing late-1940’s stock market correction featured mellow love-ballad crooners, both male and female, whose style reflected the dampened public mood.

Learn what’s really behind trends in the stock market, music, fashion, movies and more… Read Robert Prechter’s Full 50-page Report, “Popular Culture and the Stock Market,” FREE.

Robert Prechter, Chartered Market Technician, is the founder and CEO of Elliott Wave International, author of Wall Street best-sellers Conquer the Crash and Elliott Wave Principle and editor of The Elliott Wave Theorist monthly market letter since 1979.

How Punk Rock and Pop Music Relate to Social Mood and the Markets

March 10, 2011

By Elliott Wave International

We can now add the recent uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East to the category of life imitating art — specifically, music lyrics. Those who lived through the 1980s might be forgiven for hearing an unbidden snatch of music run through their heads as they watched first Hosni Mubarak and now Moammar Gadhafi try to hold onto power — “Should I Stay or Should I Go” by The Clash. In Libya, where Gadhafi has used air strikes and ground forces against the rebels, The Clash’s other huge hit from 1981, “Rock the Casbah,” describes the current situation so well it’s almost eerie:

The king called up his jet fighters

He said you better earn your pay

Drop your bombs between the minarets

Down the Casbah way

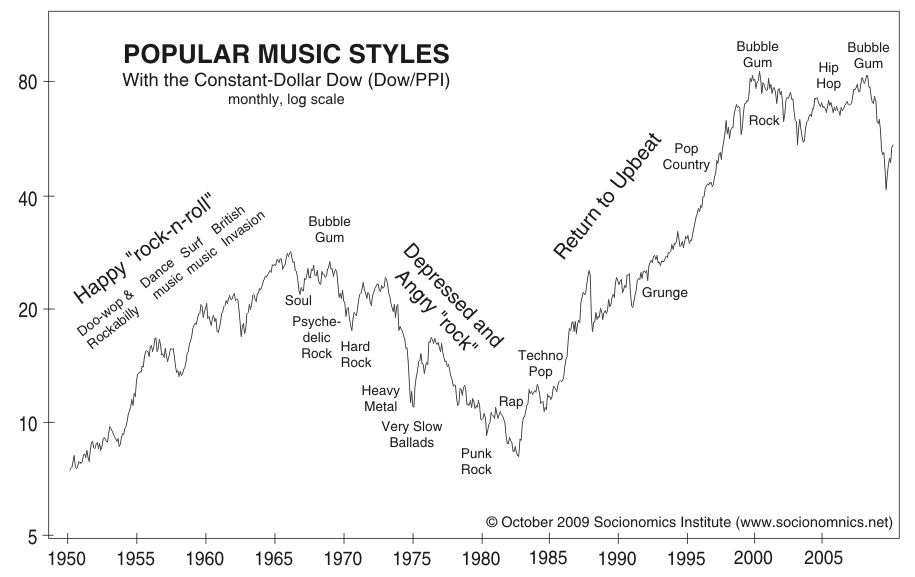

Punk rock played by bands like The Clash, X, The Ramones, and the Sex Pistols had that in-your-face, defy-authority attitude that crashed onto the scene in Great Britain and the United States in the ’70s and ’80s. It’s interesting that the lyrics can still ring true 30 years later, but even more trenchant is how the prevailing mood is reflected by the music of the times, as seen in this chart that Robert Prechter included in a talk he gave last year.

Popular culture reflects social mood, and the stock market reflects that same social mood. That’s why we get loud, angry music when people are unhappy with their situation; they want to sell stocks. We get light, poppy, bubblegum music when they feel happy and content; they want to buy stocks. In a USA Today article about music and social moods in November 2009, reporter Matt Frantz made clear the connection that Elliott Wave International has been writing about for years:

- The idea linking culture to stock prices is surprisingly simple: The population essentially goes through mass mood swings that determine not only the types of music we listen to and movies we watch, but also if we want to buy or sell stocks. These emotional booms and busts are followed by corresponding swings on Wall Street.

- “The same social elements driving the stock market are driving the gyrations on the dance floor,” says Matt Lampert, research fellow at the Socionomics Institute, a think tank associated with well-known market researcher Robert Prechter, who first advanced the idea in the 1980s. [USA Today, 11/17/09]

In the talk he gave to a gathering of futurists in Boston, Prechter explained how the music people listen to relates to social mood and the stock market:

- When the trend is up, they tend to listen to happier stuff (see chart). Back in the 1950s and ‘60s, you had doo-wop music, rockabilly, dance music, surf music, British invasion — mostly upbeat, happy material. As the value of stocks fell from the 1960s into the early 1980s, you had psychedelic music, hard rock, heavy metal, very slow ballads in the mid-1970s, and finally punk rock in the late ’70s. There was more negative-themed music. [excerpt from Robert Prechter’s speech to the World Future Society’s annual conference, 7/10/10]

Which brings us right back to punk rock. Although there’s lots of upbeat music in the air now, we can assume that after this current bear market rally, we will hear angrier music on the airwaves as the market turns down. It might be a good time, then, to pay attention to what the markets were doing the last time punk rock blasted the airwaves. Here’s an excerpt from “Popular Culture and the Stock Market,” which is the first chapter of Prechter’s Pioneering Studies in Socionomics.

- The most extreme musical development of the mid-1970s was the emergence of punk rock. The lyrics of these bands’ compositions, as pointed out by Tom Landess, associate editor of The Southern Partisan, resemble T.S. Eliot’s classic poem “The Waste Land,” which was written during the ‘teens, when the last Cycle wave IV correction was in force (a time when the worldwide negative mood allowed the communists to take power in Russia). The attendant music was as anti-.musical. (i.e., non-melodic, relying on one or two chords and two or three melody notes, screaming vocals, no vocal harmony, dissonance and noise), as were Bartok’s compositions from the 1930s.

- It wasn’t just that the performers of punk rock would suffer a heart attack if called upon to change chords or sing more than two notes on the musical scale, it was that they made it a point to be non-musical minimalists and to create ugliness, as artists. The early punk rockers from England and Canada conveyed an even more threatening image than did the heavy metal bands because they abandoned all the trappings of theatre and presented their message as reality, preaching violence and anarchy while brandishing swastikas.

- Their names (Johnny Rotten, Sid Vicious, Nazi Dog, The Damned, The Viletones, etc.) and their song titles and lyrics (“Anarchy in the U.K.,” “Auschwitz Jerk,” “The Blitzkrieg Bop,” “You say you’ve solved all our problems? You’re the problem! You’re the problem!” and “There’s no future! no future! no future!”) were reactionary lashings out at the stultifying welfare statism of England and their doom to life on the dole, similar to the Nazis backlash answer to a situation of unrest in 1920s and 1930s Germany.

- Actually, of course, it didn’t matter what conditions were attacked. The most negative mood since the 1930s (as implied by stock market action) required release, period. These bands took bad-natured sentiment to the same extreme that the pop groups of the mid-1960s had taken good-natured sentiment. The public at that time felt joy, benevolence, fearlessness and love, and they demanded it on the airwaves. The public in the late 1970s felt misery, anger, fear and hate, and they got exactly what they wanted to hear. (Luckily, the hate that punk rockers. reflected was not institutionalized, but then, this was only a Cycle wave low, not a Supercycle wave low as in 1932.)

- In summary, an “I feel good and I love you” sentiment in music paralleled a bull market in stocks, while an amorphous, euphoric “Oh, wow, I feel great and I love everybody” sentiment (such as in the late ’60s) was a major sell signal for mood and therefore for stocks. Conversely, an “I’m depressed and I hate you” sentiment in music reflected a bear market, while an amorphous tortured “Aargh! I’m in agony and I hate everybody” sentiment (such as in the late ’70s) was a major buy signal.

Popular Culture and the Stock Market. Read more about musical relationships to social mood and the markets in this 40-page-plus free report from Elliott Wave International, called Popular Culture and the Stock Market. All you have to do to read it is sign up to become a member of Club EWI, no strings attached. Find out more about this free report here.